Today is Ash Wednesday and although I did not want to provide a reading of a long poem for some time, I thought not posting on T.S. Eliot’s Ash Wednesday (1930) would be a lost opportunity. Below is a Dantean reading of Eliot’s poem. The wonder of Eliot’s poetry (like most great poetry) is that it can lead you anywhere. So read this post and take from it what you will but take a break before reading the poem. Grab a coffee, watch Downton Abbey, but try to read the poem without me in your head. I’d love to hear any interpretations. Enjoy.

Today is Ash Wednesday and although I did not want to provide a reading of a long poem for some time, I thought not posting on T.S. Eliot’s Ash Wednesday (1930) would be a lost opportunity. Below is a Dantean reading of Eliot’s poem. The wonder of Eliot’s poetry (like most great poetry) is that it can lead you anywhere. So read this post and take from it what you will but take a break before reading the poem. Grab a coffee, watch Downton Abbey, but try to read the poem without me in your head. I’d love to hear any interpretations. Enjoy.

For Eliot, Dante was more than a poetic master who had achieved the heights of poetry. As Eliot struggled through life literally searching for perfection, he rediscovered Dante, finding in his poetry not merely a poetics but also a way of life. Now, I don’t solely mean in regards to religion, in fact I am hardly concerned with religion at all. Eliot himself had written in that ‘It is wrong to think that there are parts of the Divine Comedy which are of interest only to Catholics’ and in his address ‘What Dante Means to Me’ (1950)—after his religious conversion—he stated, ‘to call [Dante] a “religious poet” would be to abate his universality.’ Eliot looked to Dante because Dante had succeeded in attaining the closest thing a poet could to poetical perfection, and he had done it regardless of the social and personal complexities of life. Eliot, initially captivated by Dante’s poetics, would come to grow engrossed by the man as their respective lives began to mirror one another to the extent that the modern and the medieval can.

Although Eliot’s early poetry uses many religious themes and motifs, it is not until 1925 that his poetry begins to convey any sort of leaning toward a single dogma. In fact, Eliot had regarded Buddhism as perhaps the most compelling form of spiritualism at the time of The Waste Land. Given these early, protean views, readers rising out of The Waste Land and moving directly into Ash Wednesday will experience one of poetry’s most difficult transitions in regards to philosophical positioning; however ambivalence may be what Eliot is attempting to convey, as it is his belief that the highest stage possible for the civilized man ‘is to unite the profoundest skepticism with the deepest faith.’

In 1925—two years prior to his conversion and the subsequent writing of what is now part II of Ash Wednesday—Eliot had begun to reassess his studies of Dante. Sometime between 1926 and 1929 (the year Eliot published his most substantial work on Dante), he would come to parallel his beliefs most fundamentally with those of Dante’s. It is likely that—on some level—Dante influenced Eliot’s religious conversion. Despite its religious leanings, Ash Wednesday—as Eliot says of Dante’s Paradiso—is not didactic. The religious, Dantean themes in Ash Wednesday have been thoroughly excavated by scholars, as the allusions are relatively more palpable than they are in his other poetry. However, what is most important is that in Ash Wednesday Eliot searches for (and seems to gain) a particular assurance that his poetry can bridge the gap between the ‘low-dream’ of the modern world and the ‘high-dream’ of Dante’s vision. Ash Wednesday marks Eliot’s personal-poetic search for the ability to materialize the Word Incarnate with the written word.

In 1925—two years prior to his conversion and the subsequent writing of what is now part II of Ash Wednesday—Eliot had begun to reassess his studies of Dante. Sometime between 1926 and 1929 (the year Eliot published his most substantial work on Dante), he would come to parallel his beliefs most fundamentally with those of Dante’s. It is likely that—on some level—Dante influenced Eliot’s religious conversion. Despite its religious leanings, Ash Wednesday—as Eliot says of Dante’s Paradiso—is not didactic. The religious, Dantean themes in Ash Wednesday have been thoroughly excavated by scholars, as the allusions are relatively more palpable than they are in his other poetry. However, what is most important is that in Ash Wednesday Eliot searches for (and seems to gain) a particular assurance that his poetry can bridge the gap between the ‘low-dream’ of the modern world and the ‘high-dream’ of Dante’s vision. Ash Wednesday marks Eliot’s personal-poetic search for the ability to materialize the Word Incarnate with the written word.

Eliot’s view that ‘all faith should be seasoned with a skillful sauce of skepticism’ is what makes the first line of Ash Wednesday and the position of the speaker’s philosophy throughout so difficult to fully ascertain. Eliot institutes several disjunctive techniques as a type of objective correlative that sustains the vacillating nature of the speaker’s mind. These are the overlay of space and place, a lack of linearity, and ambiguous lexicon or multiple entendre. The ‘turn’ in the opening line of Ash Wednesday denotes the linchpin around which the whole poem rotates: ambiguity. The turn will come to signify the turning toward God, the look to a secular past, glimpses toward the future and many other possibilities. Most importantly, the turn is the repetitious but non-retrogressive movement from the active will to the contemplative mind.

Part I portrays the struggle between the individual’s will and intellect, collating the two pressing skepticisms within its ambiguity. That Eliot begins Ash Wednesday with an almost direct translation of Calvacanti followed by an almost direct quote from Shakespeare, marks Eliot’s first skepticism. The ‘gift’ Eliot desires to be gifted with is poetry that can transcend to heaven. Through the rewriting of text, Eliot tries to attain ‘a conception of poetry as a living whole of all the poetry that has ever been written.’ The word of the poet and the transcendent Word are wholly deliberated upon in both the fourth poem, in which the pure poetic imagination is considered, and the fifth poem, where the poet’s adequacy in the expression of reality is questioned. This questioning of his poetic transcendence is most explicitly present in his humility at the gate of Purgatory in the third poem: ‘Lord, I am not worthy / Lord, I am not worthy / but speak the word only.’

The passage through the gate of Purgatory will mark the full religious conversion and it is figured within a poem that is an exodus more fully realized than The Waste Land; the exodus here is one of necessary, willful expiation, as for Eliot the ascetic way of penance is the means to the way of grace. The will (which wavered in the opening poem) is strengthened in the final two lines, representing not the altered word of some poet but rather the pure speech of transcendence through the voice of the Churches invocation of Mary: ‘Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.’ The death is the spiritual death leading to baptismal rebirth that Eliot had feared (‘Why should the aged eagle stretch its wings?’) out the outset.

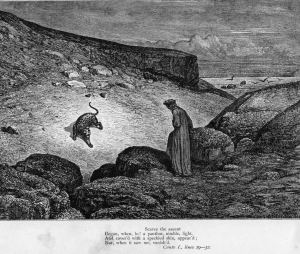

The second poem of Ash Wednesday was originally titled ‘Salutation’, referring to the first time Beatrice greets Dante in La Vita Nuova III: ‘with a salutation of such virtue that I thought then to see the world of blessedness.’ In La Vita Nuova, Dante struggles twice with the desire of the physical; first with Beatrice and later with a mysterious lady to whom he is attracted. It is possible that Eliot’s renunciation of the ‘blessèd face’ is in fact the physical face, which Dante renounced in order to attain salvation, and not a turning from the spiritual face.  The ‘three white leopards,’ might be read as a positive inverse of the leopard of lust of Dante’s Inferno, representing a violent though willful expiation of lust. After the leopards have ‘fed to satiety on my heart my liver and that which had been contained / In the hollow round of my skull,’ the left over bones ‘shine with brightness’ because of the virtuousness of the Lady. The now pure essence of the speaker—the ‘I who am’—is able to ‘Proffer [his] deeds to oblivion’ and his ‘love / To the posterity of the desert,’ which is at once in ‘The desert in the garden [and] the garden in the desert’ brought about by Mary, ‘The single Rose’ who is now ‘the Garden / Where all loves end.’

The ‘three white leopards,’ might be read as a positive inverse of the leopard of lust of Dante’s Inferno, representing a violent though willful expiation of lust. After the leopards have ‘fed to satiety on my heart my liver and that which had been contained / In the hollow round of my skull,’ the left over bones ‘shine with brightness’ because of the virtuousness of the Lady. The now pure essence of the speaker—the ‘I who am’—is able to ‘Proffer [his] deeds to oblivion’ and his ‘love / To the posterity of the desert,’ which is at once in ‘The desert in the garden [and] the garden in the desert’ brought about by Mary, ‘The single Rose’ who is now ‘the Garden / Where all loves end.’

In Part III, the speaker has awoken from the dream of contemplation at the violet hour and come face-to-face with three stairs of the active will. The progression of the winding staircase holds in the balance the presence of a metaphysical poetry within the modern world. ‘The broadbacked figure drest in blue and green’ who enchants ‘the maytime with an antique flute’ is not only a look back to secular desires— figured here in pagan imagery—which once enchanted the heart, but, if it is succumbed to would assert that modern poetry is only capable of the ‘low-dream.’ For this reason the look back to the pagan imagery on the third stair can  only be glimpsed through a ‘slotted window bellied like a fig’s fruit’ (109); the vision is impeded upon by the narrowed window of secularism because both the will and the intellect are torn between the secular wor(l)d and the Wor(l)d of God. As Eliot climbs the third stair, having gathered the ‘strength beyond hope and despair,’ he is able to humbly admit that he can ‘speak the word only’. After this admission, he is able to re-experience for himself the vision of God’s Word that he had only evinced through Ezekiel beneath the juniper tree, and he recapitulates the experience through the great mediator of the Word (Dante) who Eliot considered to have the gift of incarnation.

only be glimpsed through a ‘slotted window bellied like a fig’s fruit’ (109); the vision is impeded upon by the narrowed window of secularism because both the will and the intellect are torn between the secular wor(l)d and the Wor(l)d of God. As Eliot climbs the third stair, having gathered the ‘strength beyond hope and despair,’ he is able to humbly admit that he can ‘speak the word only’. After this admission, he is able to re-experience for himself the vision of God’s Word that he had only evinced through Ezekiel beneath the juniper tree, and he recapitulates the experience through the great mediator of the Word (Dante) who Eliot considered to have the gift of incarnation.

While walking ‘between the violet and the violet’ in a garden where the ‘fiddles and the flutes’ of the pagan scene have been ‘bear[ed] away’, Eliot is able to initiate his transcendence. His memories of the previous years are restored through a ‘bright of cloud tears’ and he subsequently will be able to write ‘With a new verse the ancient rhyme’ in order to ‘Redeem / The unread vision in the higher dream.’ Then the Lady, Word of no speech, ‘signed but spoke no word.’ Logos is witnessed but it is still mediated through an Other.

However, he does not experience the transcendental movement into the still point of Incarnation. He is still aware of the ‘the empty forms’ of the secular world and also that through the process of memory he may renew the ‘salt savour of the sandy earth.’ In this moment, when face-to-face with a carnal past, ‘the weak spirit quickens to rebel.’ It is not until the crucial moment when he ‘[spits] from the mouth the withered apple-seed’ thereby purging himself of humanity’s first failure that he can attempt to reach Logos on a personal and intellectual level.

Here’s the poem.

Ash Wednesday

I

Because I do not hope to turn again

Because I do not hope

Because I do not hope to turn

Desiring this man’s gift and that man’s scope

I no longer strive to strive towards such things

(Why should the aged eagle stretch its wings?)

Why should I mourn

The vanished power of the usual reign?

Because I do not hope to know again

The infirm glory of the positive hour

Because I do not think

Because I know I shall not know

The one veritable transitory power

Because I cannot drink

There, where trees flower, and springs flow, for there is nothing again

Because I know that time is always time

And place is always and only place

And what is actual is actual only for one time

And only for one place

I rejoice that things are as they are and

I renounce the blessed face

And renounce the voice

Because I cannot hope to turn again

Consequently I rejoice, having to construct something

Upon which to rejoice

And pray to God to have mercy upon us

And pray that I may forget

These matters that with myself I too much discuss

Too much explain

Because I do not hope to turn again

Let these words answer

For what is done, not to be done again

May the judgement not be too heavy upon us

Because these wings are no longer wings to fly

But merely vans to beat the air

The air which is now thoroughly small and dry

Smaller and dryer than the will

Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still.

Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death

Pray for us now and at the hour of our death.

II

Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree

In the cool of the day, having fed to satiety

On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained

In the hollow round of my skull. And God said

Shall these bones live? shall these

Bones live? And that which had been contained

In the bones (which were already dry) said chirping:

Because of the goodness of this Lady

And because of her loveliness, and because

She honours the Virgin in meditation,

We shine with brightness. And I who am here dissembled

Proffer my deeds to oblivion, and my love

To the posterity of the desert and the fruit of the gourd.

It is this which recovers

My guts the strings of my eyes and the indigestible portions

Which the leopards reject. The Lady is withdrawn

In a white gown, to contemplation, in a white gown.

Let the whiteness of bones atone to forgetfulness.

There is no life in them. As I am forgotten

And would be forgotten, so I would forget

Thus devoted, concentrated in purpose. And God said

Prophesy to the wind, to the wind only for only

The wind will listen. And the bones sang chirping

With the burden of the grasshopper, saying

Lady of silences

Calm and distressed

Torn and most whole

Rose of memory

Rose of forgetfulness

Exhausted and life-giving

Worried reposeful

The single Rose

Is now the Garden

Where all loves end

Terminate torment

Of love unsatisfied

The greater torment

Of love satisfied

End of the endless

Journey to no end

Conclusion of all that

Is inconclusible

Speech without word and

Word of no speech

Grace to the Mother

For the Garden

Where all love ends.

Under a juniper-tree the bones sang, scattered and shining

We are glad to be scattered, we did little good to each other,

Under a tree in the cool of the day, with the blessing of sand,

Forgetting themselves and each other, united

In the quiet of the desert. This is the land which ye

Shall divide by lot. And neither division nor unity

Matters. This is the land. We have our inheritance.

III

At the first turning of the second stair

I turned and saw below

The same shape twisted on the banister

Under the vapour in the fetid air

Struggling with the devil of the stairs who wears

The deceitul face of hope and of despair.

At the second turning of the second stair

I left them twisting, turning below;

There were no more faces and the stair was dark,

Damp, jagged, like an old man’s mouth drivelling, beyond repair,

Or the toothed gullet of an aged shark.

At the first turning of the third stair

Was a slotted window bellied like the figs’s fruit

And beyond the hawthorn blossom and a pasture scene

The broadbacked figure drest in blue and green

Enchanted the maytime with an antique flute.

Blown hair is sweet, brown hair over the mouth blown,

Lilac and brown hair;

Distraction, music of the flute, stops and steps of the mind over the third stair,

Fading, fading; strength beyond hope and despair

Climbing the third stair.

Lord, I am not worthy

Lord, I am not worthy

but speak the word only.

IV

Who walked between the violet and the violet

Who walked between

The various ranks of varied green

Going in white and blue, in Mary’s colour,

Talking of trivial things

In ignorance and knowledge of eternal dolour

Who moved among the others as they walked,

Who then made strong the fountains and made fresh the springs

Made cool the dry rock and made firm the sand

In blue of larkspur, blue of Mary’s colour,

Sovegna vos

Here are the years that walk between, bearing

Away the fiddles and the flutes, restoring

One who moves in the time between sleep and waking, wearing

White light folded, sheathing about her, folded.

The new years walk, restoring

Through a bright cloud of tears, the years, restoring

With a new verse the ancient rhyme. Redeem

The time. Redeem

The unread vision in the higher dream

While jewelled unicorns draw by the gilded hearse.

The silent sister veiled in white and blue

Between the yews, behind the garden god,

Whose flute is breathless, bent her head and signed but spoke no word

But the fountain sprang up and the bird sang down

Redeem the time, redeem the dream

The token of the word unheard, unspoken

Till the wind shake a thousand whispers from the yew

And after this our exile

V

If the lost word is lost, if the spent word is spent

If the unheard, unspoken

Word is unspoken, unheard;

Still is the unspoken word, the Word unheard,

The Word without a word, the Word within

The world and for the world;

And the light shone in darkness and

Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled

About the centre of the silent Word.

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Where shall the word be found, where will the word

Resound? Not here, there is not enough silence

Not on the sea or on the islands, not

On the mainland, in the desert or the rain land,

For those who walk in darkness

Both in the day time and in the night time

The right time and the right place are not here

No place of grace for those who avoid the face

No time to rejoice for those who walk among noise and deny the voice

Will the veiled sister pray for

Those who walk in darkness, who chose thee and oppose thee,

Those who are torn on the horn between season and season, time and time, between

Hour and hour, word and word, power and power, those who wait

In darkness? Will the veiled sister pray

For children at the gate

Who will not go away and cannot pray:

Pray for those who chose and oppose

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Will the veiled sister between the slender

Yew trees pray for those who offend her

And are terrified and cannot surrender

And affirm before the world and deny between the rocks

In the last desert before the last blue rocks

The desert in the garden the garden in the desert

Of drouth, spitting from the mouth the withered apple-seed.

O my people.

VI

Although I do not hope to turn again

Although I do not hope

Although I do not hope to turn

Wavering between the profit and the loss

In this brief transit where the dreams cross

The dreamcrossed twilight between birth and dying

(Bless me father) though I do not wish to wish these things

From the wide window towards the granite shore

The white sails still fly seaward, seaward flying

Unbroken wings

And the lost heart stiffens and rejoices

In the lost lilac and the lost sea voices

And the weak spirit quickens to rebel

For the bent golden-rod and the lost sea smell

Quickens to recover

The cry of quail and the whirling plover

And the blind eye creates

The empty forms between the ivory gates

And smell renews the salt savour of the sandy earth This is the time of tension between dying and birth The place of solitude where three dreams cross Between blue rocks But when the voices shaken from the yew-tree drift away Let the other yew be shaken and reply.

Blessed sister, holy mother, spirit of the fountain, spirit of the garden,

Suffer us not to mock ourselves with falsehood

Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still

Even among these rocks,

Our peace in His will

And even among these rocks

Sister, mother

And spirit of the river, spirit of the sea,

Suffer me not to be separated

And let my cry come unto Thee.

Ash-Wednesday, from Collected Poems 1909-1962 by T S Eliot, © T S Eliot 1963, Faber & Faber Limited

The question of the appeal of modern poetry is a very big concern among modernists and a common question among readers new to the genre. Many prefer the aesthetics of the Elizabethan’s, enjoying the sing-song simplicity and rhyme. Often, when I tell people that I am passionate about modern poetry they ask, ‘Why?’ Some objectors of the place of poetry even use (in so many words) W.H. Auden’s line in his elegy to W.B. Yeats, seemingly unaware of the contradiction: ‘poetry makes nothing happen.’

The question of the appeal of modern poetry is a very big concern among modernists and a common question among readers new to the genre. Many prefer the aesthetics of the Elizabethan’s, enjoying the sing-song simplicity and rhyme. Often, when I tell people that I am passionate about modern poetry they ask, ‘Why?’ Some objectors of the place of poetry even use (in so many words) W.H. Auden’s line in his elegy to W.B. Yeats, seemingly unaware of the contradiction: ‘poetry makes nothing happen.’